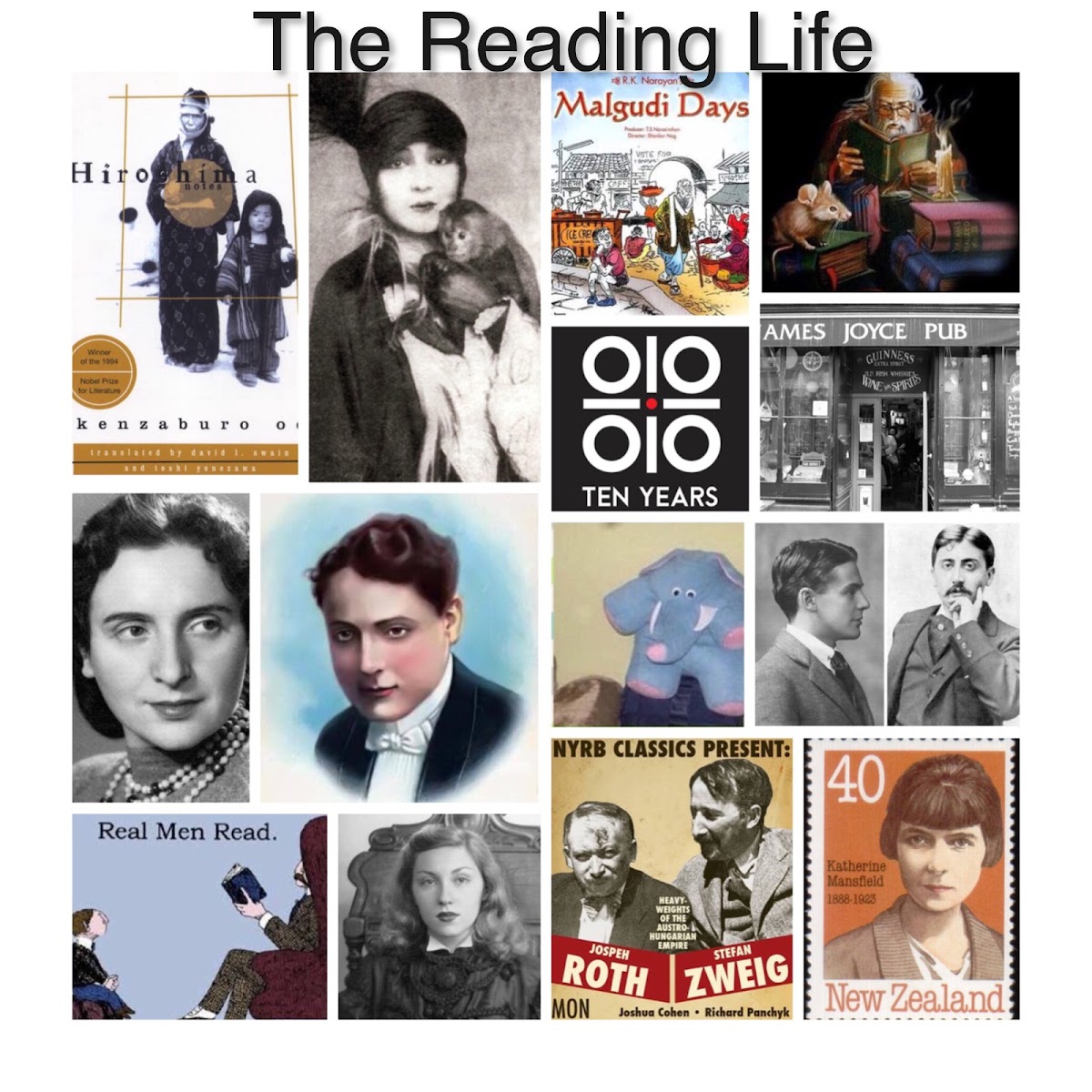

"Crazy Iris" by Masuji Ibuse is the lead story in

The Crazy Iris and Other Stories of the Atomic Age which was edited and introduced by Kenzaburo Oe. (1985, Grove Press) All of the short stories in the book were selected by Oe and deal with the effects of the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb experience on August 6, 2009 on those who lived through it. Several of the authors whose stories are included in the collection were in Hiroshima or near it that day. Oe also provides an introduction to the book in which he tells us a little about each writer and their personal background and life history. I was so excited when I found this book in a mall book store last week. It really is a perfect book for someone like me who wants to learn about Japanese literature. The book contains stories by eight different authors considered very talented by Mr Oe. In most cases he knows them.

The author of "Crazy Iris" Masuji Ibuse was born in Hiroshimi and, like Oe studied French literature and also had a deep interest in the work of Tolstoy. He was born 1898 and died 1993. During WWII he served in Singapore in the Japanese Army. His primary duty as writer for the Singapore newspaper

The Straights Times. He wrote articles in which he depicted the occupation of the city by the Japanese as very preferable for the people to British rule via a diary he published. As time went on he stopped publishing his diary as he saw no point to doing it under military supervision. He also gave lectures on Japanese culture at a Singapore University. He was an unwilling inductee into the Japanese army and he showed his distaste for military life in his writings after the war. He did not directly experience the blast as he was in Singapore on August 6, 1845. He never was in combat.

There is a codified language of flowers made use of in Japanese literature and art (and even in tattoos).

Different flowers mean different things. These meanings would be part of the assumed cultural background of the original readers of "Crazy Iris". It is common cultural knowledge among Japanese readers and the authors of the works in this collection would all assume their readers understood it. This knowledge is not, at least in my case, something I learned as a child in early schooling, so I did a bit of research to discover the possible symbolic meaning of the Iris in Japanese literature. In the symbolic language of flowers, hanakotoba, the iris stands for strength, vitality, boldness and power. In rural Japan, where "Crazy Iris" is set, it was considered protection from typhoons and storms and was often planted on roof tops. It is also considered a symbol of royal warriors. Like Oe, Masuji Ibuse evokes echos from Western mythology and history in his use of floral images, super imposing two traditions into one or in some cases using the western traditiion as a haunted mirror image of the Japanese. In ancient Greece Iris was, among other things the goddess of the rainbow and the messenger of the gods. In ancient Egypt and much of India the iris symbolized resurrection. In post war Japan the old faiths were destroyed. In these circumstances in many cultures people seek out roots and myths that predate those that let them down. I think the same thing happened to Oe and Ibuse and other Japanese writers. If we look deep enough into their stories we will see roots in ancient cults and animism. It is no accident that Yeats and Blake are Oe's English poets.

"Crazy Iris" begin on the morning of August 6, 1945, the day of the first atomic bomb blast. It is set in a rural town about 100 miles from Hiroshima. The people of the town had been advised the day before to evacuate as a heavy fire bomb raid from the Americans was expected soon. The Americans even dropped leaflets telling people to move. As the story begins our narrator is at a store owned by a friend of his. Everything but food is very cheap. The shop keeper tells him might as well sell everything before his store is burned by the bombs. The people of the town had all been told to take the train to Hiroshima where it was felt they would be safer. The people are frustrated to hear that all trains going to Hiroshima have been stopped. At first they do not know what has happened to cause this. Our narrator goes to visit a dental clinic owned by an old friend of his.

Just a few days before, his only son, who had volunteered as a junior pilot, was killed and the news seemed to have taken the life out of him. I felt if the air raid siren were to sound this very moment, he would not take shelter but continue to stand there leaning on the table.

Here is how he first heard of the bomb blast:

In fact I did not hear of the destruction of Hiroshima until thirty or forty hours after the event. We in our village first learned what had happened indirectly from one of the victims who had fled to a neighboring village. He reported some strange weapon had been exploded and that from one moment to the next Hiroshima had ceased to exist.

Survivors of the blast began to spread out to neighboring towns. Many of the people who lived and worked in Hiroshima were from the smaller towns near it and he wanted to return home to look for help and face death among those they knew.

Kobayashi had no idea where he was going...He was aware of a peculiar pain throughout his body. Something told him he was going to die. Whatever happened he must make his way back to his home village and his family! He managed to get a ride on a truck to Fukuyama and from there he took an army truck hom. He returned covered with blood. He immediately visited Dr. Tawa, the village doctor, but the latter had no idea how to treat him.

The residents of Fukuyama do not really understand yet what has happened. The biggest topic of conversation is "where will it happen next". Soon they hear of the surrender. Our narrator begins to develop stomach problems he will never get rid of right after hears the news. Many others flood the doctor's office with complaints that seem to have no cause the doctor can find. Many will have them the rest of their lives.

Life goes on. Ten months after the surrender our narrator goes to visit Hiroshima to see it for himself.

I remember how impressed I was to find that of all the trees in Hiroshima, the palms alone, though charred and twisted, had withstood the tremendous temperature of a year before and were now putting forth buds.

We see some interesting events unfold that can tell us a lot about life in the immediate post war period. It was very interesting, for example, to see how Japanese policemen are now treated by the people. They once were regarded as agents of the Imperial God of Japan and were greatly feared. Our narrator was from Tokyo had had moved out when the war started. (We never learn much about him. We do not know if he had a family or a role in the war efforts. I guess he is in his 60s. We never learn his occupation or economic status.)

A week after the blast he decides it is time to go back to Tokyo. He stays with an old friend who lives next to a pond. One morning he gets up early and sees a body floating in the pond. The iris are all clustered at one end of the pond. They all call the police. Then they notice one of the iris is in bloom.

"Did you know there is an iris in bloom", the old man's voice voice came up. "It's amazing! Think of an iris blooming at this time of year!"

We learn the body in the pond was that of just another person driven mad by the blast.

"I gather she was a half-crazy girl. Her parents had sent her to work in Hiroshima to work in a factory and she was there the day the atomic bomb exploded"

What is more interesting to our narrator and his friend is what has happened to the iris in the pond

At the mouth of the gulley grew the angular leaves from whose recess emerged the twisted stem with its belated purple flowers. The petals looked hard and crinkly..."Do you think they were frightened into bloom?..I have never heard of an Iris flowering this late. It must have gone crazy! ..When I told Mr Kiuchi this incident he turned to me and said "The iris blooming is crazy and it belongs to a crazy age"

The crazy iris evokes a world in which warrior traditions are destroyed and old folk beliefs about the protective power of flowers are turned into a graveyard joke. The atomic bomb somehow seems an inverted iris. A messenger from long ago and far ahead that will have to be reread into the language of flowers.

There are a lot of interesting details in this twenty page short story. We get a real feel for how it must have felt to be 100 miles from the blast in a small town in rural Japan. "Crazy Iris" was first published in 1951. Masuji Ibuse lived a very long time and became a revered figure in Japanese literary circles. His best known work was a novel about the effects of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Black Rain. I will read it soon I hope. There are other thematic veins that could be mined in this story. For example, there are clear symbolic meanings in the reference to palm trees as the only surviving trees These references are very interesting in that they suggest that Ibuse is evoking ancient themes from traditions other than his own. Maybe the story is in part, as are the stories of Oe I have read, about the recreation of life supporting faiths and myths after the accepted ones are made hollow. These matters all tie directly into Reading Life questions.

U C L A students are reading, as of September 2014, this post in large numbers. I hope they will share theirs reaction to this and related stories with us

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_b.png?x-id=3e3a9870-13a9-88fd-9c80-621447478d58)